Size matters in the detection of exoplanet atmospheres

26 September 2017

A group-analysis of 30 exoplanets orbiting distant stars suggests that size, not mass, is a key factor in whether a planet’s atmosphere can be detected according to a UCL-led team of European researchers.

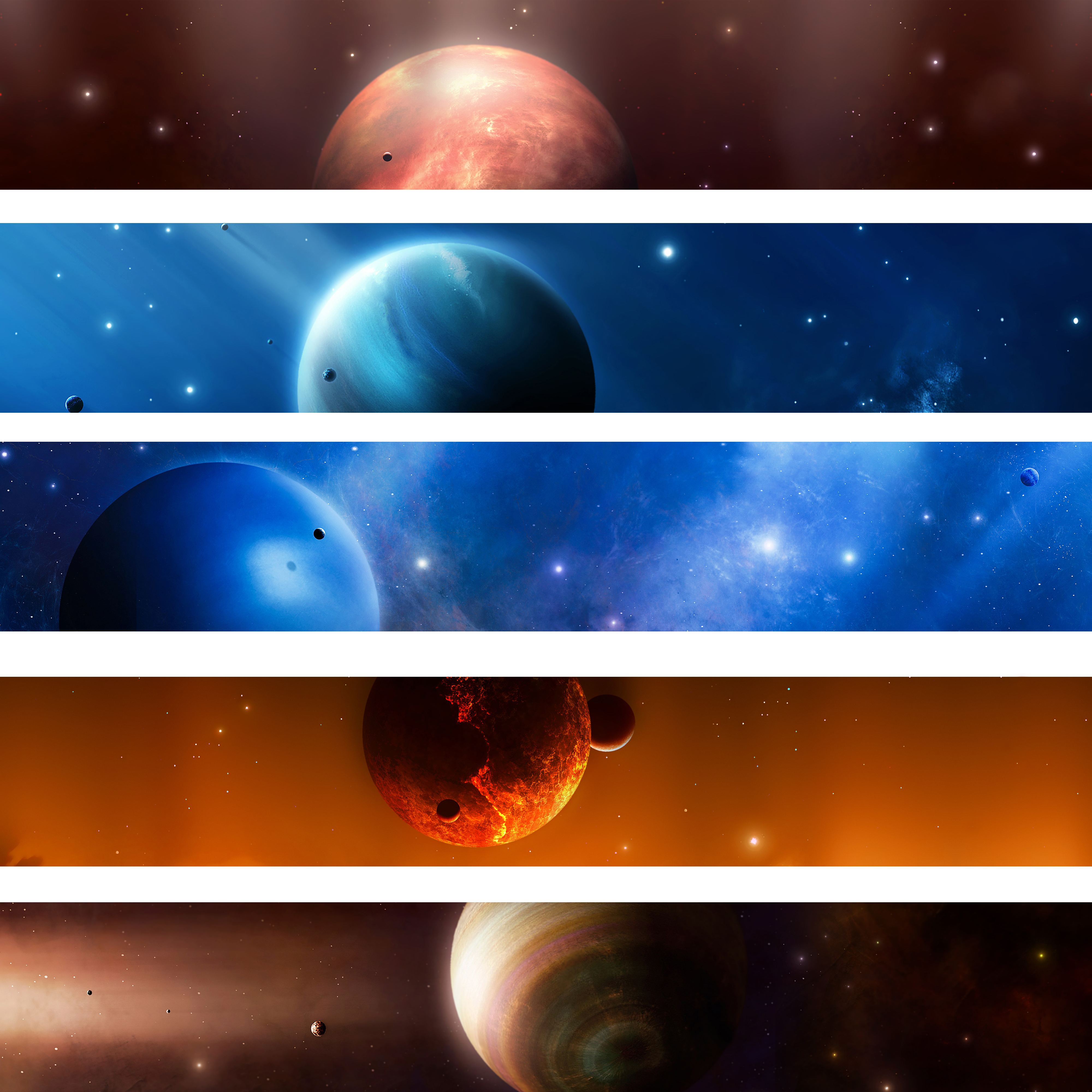

Hot Jupiter exoplanets The largest population-study of exoplanets to date successfully detected atmospheres around 16 ‘hot Jupiters’, and found that water vapour was present in every case.

The findings, presented last week at the European Planetary Science Congress, have important implications for the comparison and classification of diverse exoplanets.

“More than 3,000 exoplanets have been discovered but, so far, we’ve studied their atmospheres largely on an individual, case-by-case basis. Here, we’ve developed tools to assess the significance of atmospheric detections in catalogues of exoplanets,” said Angelos Tsiaras, the lead author of the study and PhD student in UCL Physics & Astronomy and the Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL/Birkbeck (CPS). “This kind of consistent study is essential for understanding the global population and potential classifications of these foreign worlds.”

The researchers used archive data from the ESA/NASA Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) to retrieve spectral profiles of 30 exoplanets and analyse them for the characteristic fingerprints of gases that might be present. About half had strongly detectable atmospheres.

Results suggest that while atmospheres are most likely to be detected around planets with a large radius, the planet’s mass does not appear to be an important factor. This indicates that a planet’s gravitational pull only has a minor effect on its atmospheric evolution.

Most of the atmospheres detected show evidence for clouds. However, the two hottest planets, where temperatures exceed 1,700 degrees Celsius, appear to have clear skies, at least at high altitudes. Results for these two planets indicate that titanium oxide and vanadium oxide are present in addition to the water vapour features found in all 16 of the atmospheres analysed successfully.

“To understand planets and planet formation we need to look at many planets: at UCL we are implementing statistical tools and models to handle the analysis and interpretation of large sample of planetary atmospheres. 30 planets is just the start,” said Dr Ingo Waldmann (UCL Physics & Astronomy and the CPS), a co-author of the study.

“30 exoplanet atmospheres is a great step forward compared to the handful of planets observed years ago, but not yet big-data. We are working at launching dedicated space missions in the next decade to bring this number up to hundreds or even thousands,” commented Professor Giovanna Tinetti (UCL Physics & Astronomy and the CPS).

Links

Professor Giovanna Tinetti’s academic profile

Dr Ingo Waldmann’s academic profile

European Planetary Science Congress

Image

An artist’s impression of hot Jupiter exoplanets (credit: alexaldo)

Media contact

Bex Caygill Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3846 Email: r.caygill [at] ucl.ac.uk